Abraham Lincoln

19th c. lawyer, statesman, and President of the United States who reunited a fractured nation and led efforts in achieving a Constitutional amendment to formally abolish slavery.

As a lawyer, statesman and, ultimately, the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln's initial vision of unity was born out of a desire to protect and defend the constitutional democracy envisioned by the Founders. Seeing Southern secession as a threat to the Union, and slavery as incompatible with the country's founding principles, Lincoln dedicated himself to completing the Founders' vision of a nation both united and free.

Yet as the Civil War emerged and escalated, so did Lincoln's anguish in his efforts to preserve a united nation. By the time he delivered his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln had come to see the horrific casualties of the Civil War as part of a larger plan—a sovereign God's costly lesson to the North and South for their participation, both tacit and explicit, in the act of slavery. His speech has been called “America’s Sermon” and makes multiple references to biblical passages and ideals that informed his conviction. To truly unite the nation in peace and equality, Lincoln believed all people would need to come together in the spirit of reconciliation and compassion. Only then would the nation heal, and begin to realize the long-declared rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Print showing Union troops advancing from the right while fighting at the battle of Gettysburg.

The battle of Gettysburg. Gettysburg Pennsylvania United States, ca. 1867. N.Y.: Published by Thomas Kelly, 264 Third Avenue, between 22nd & 23rd St., N.Y.: Printed by Wm. C. Robertson, 59 Cedar St. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006681070/

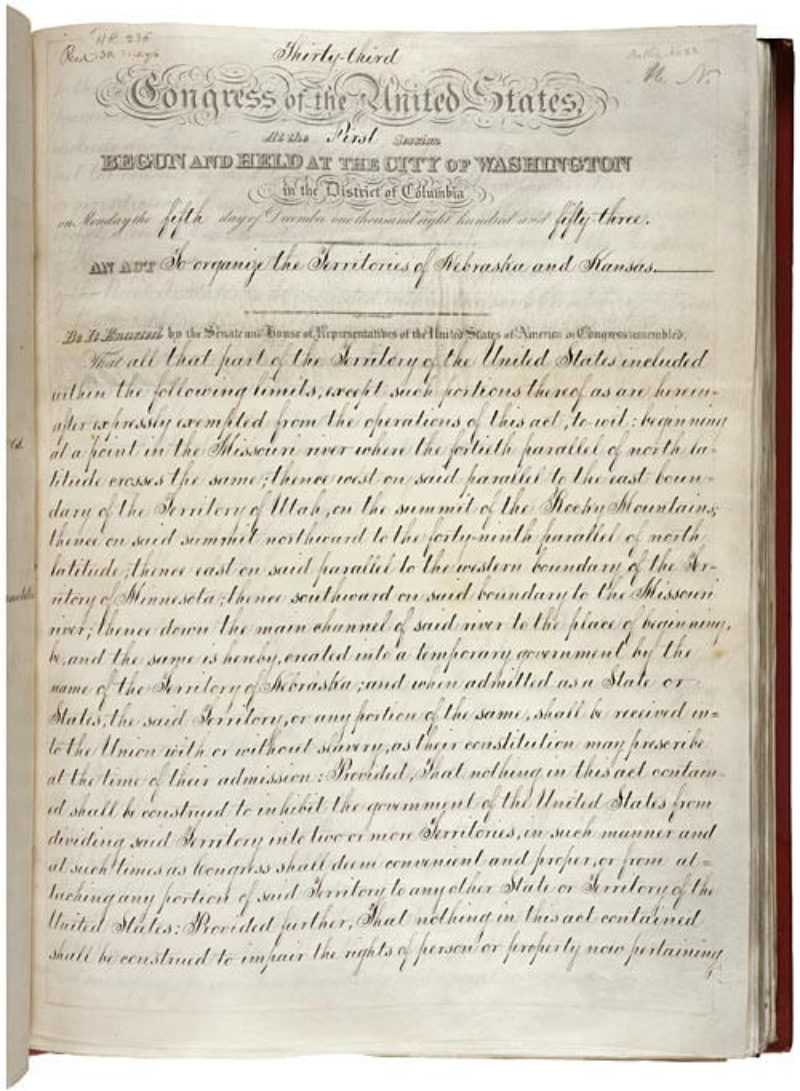

Abraham Lincoln’s path to the presidency began in 1854, when the passage of the Kansas- Nebraska Act drew him away from his private law practice, and into the political arena. This new bill authorized the creation of the Kansas and Nebraska territories, and mandated “popular sovereignty,” a concept that allowed settlers of each new territory to decide whether or not slavery would be permitted within their borders. Settlers on both sides of the slavery debate rushed into the new territories, hoping to sway the decision to make a state slave or free. Rival governments rose in the contested Kansas territories, and violent clashes between rival political parties Whigs and Democrats led to hundreds of deaths.

As the last painting in his Election Series, Caleb Bingham’s The Verdict of the People tells the end of the story represented in the series. Within this painting, the artist hid several political motives and ideas. The painting depicts public reaction to a proslavery candidate's likely election victory. Completed in 1854, the work covered issues of slavery, temperance, and a representative government, subjects that had gone from a local to a national level in public debate.

Image courtesy of St. Louis Art Museum

The Kansas-Nebraska Act.

An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas, 1854; Record Group 11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives

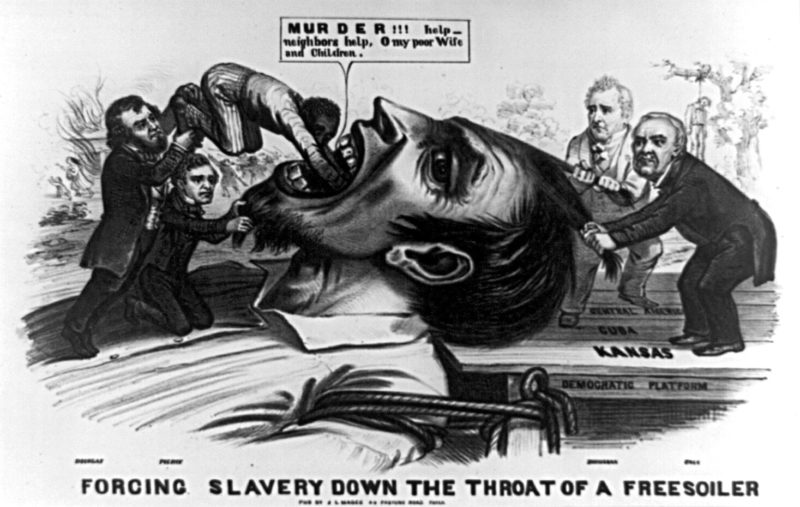

An 1856 cartoon depicts an abolitionist or "free-soiler" being force-fed slavery by Democratic party leaders.

Magee, John L. Forcing Slavery Down the Throat of a Freesoiler, August 1856, American political prints, 1766-1876 by Bernard F. Reilly. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/

A self-made man, Lincoln valued the right of any citizen to improve their condition in society. He also saw the existence of slavery as contradictory to the Declaration’s founding principle that “all men are created equal,” and he opposed slavery’s spread to non-slaveholding states. In 1856, Lincoln joined the newly formed Republican Party, which took an active anti-slavery stance. His fellow party members elected him to run in the Illinois Senate race against three-term incumbent Stephen Douglas.

The large, bold woodcut image of a supplicant male slave in chains appears on the American 1837 broadside publication of John Greenleaf Whittier's antislavery poem, "Our Countrymen in Chains." The design was originally adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England in the 1780s, and appeared on several medallions for the society made by Josiah Wedgwood as early as 1787.

Am I Not a Man and a Brother? 1837. Retrieved from Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Washington, D.C.

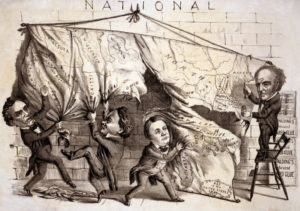

During that campaign, Lincoln and Douglas engaged in seven debates throughout Illinois regarding the future of slavery. Lincoln’s highly publicized speeches during this time stirred the hearts of the Illinois electorate—in particular, his famous “House Divided” speech in June of 1858. In that speech, Lincoln drew from imagery in the biblical texts of Matthew 12:25 and Mark 3:25 to caution that these divisive battles over slavery would continue to tear the nation apart.

This 1860 cartoon, “Dividing the National Map,” depicts the election between Abraham Lincoln and his opponent, Stephen Douglas. Their parties’ differing views on slavery reflected the tearing apart of the nation into pro- and anti-slavery factions.

“Dividing the National Map,” cartoon, 1860, zoomable image, House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/33155

Abraham Lincoln at a Lincoln-Douglas Debate

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Lincoln lost the Illinois senatorial election of 1858. But his growing political capital in the North led to his nomination in May of 1860 as the Republican Presidential candidate. The news of Lincoln’s nomination and later campaign victory inflamed tensions between the Northern and Southern states.

In an attempt to ease tensions between opposing factions in the North and South, Lincoln remained silent on the contentious issue of slavery leading up to his inauguration. But between November of 1860 and his inauguration in March of 1861, seven states still seceded from the United States to form the Confederate States of America.

In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln finally spoke out against the secession. The Constitution, he argued, established a “perpetual union” and not a mere contract. This Union even predated the Constitution, stretching back before the American Revolution to “every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land.” A constitutional democracy, he reasoned, could not endure if the minority simply ignored these binding commitments when they became dissatisfied with the vote of the majority. The people had to work together to overcome their differences and accomplish their vision of a “more perfect Union.”

Lincoln did not discuss his own faith during this period, but in the First Inaugural Address he evokes the concept of common faith as integral to the Union. Americans, he claimed, share a sense of spiritual unity and direction under God. Lincoln reasons, “Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land are still competent to adjust in the best way all our present difficulty.” The new president appeals for a public confidence in superintending Divine justice, “If the Almighty Ruler of Nations, with His eternal truth and justice, be on your side of the North, or on yours of the South, that truth and that justice will surely prevail by the judgment of this great tribunal of the American people. As Lincoln began his first days in office and despite his hopes, it was becoming apparent that the crisis would not be resolved without bloodshed.

A month into Lincoln’s first term as president, the tensions between the Union and Confederate factions boiled over, starting what would become the bloodiest war in American history. At the start of the Civil War, Lincoln had one goal: to preserve the Union. Yet as the conflict stretched from months into years, the sheer number of causalities and the effort of reunifying the country became an increasing burden on Lincoln’s soul.

An African American family headed to Union lines in an attempt to become free.

Woodbury, David B., A Negro family coming into the Union lines, January 1, 1863, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

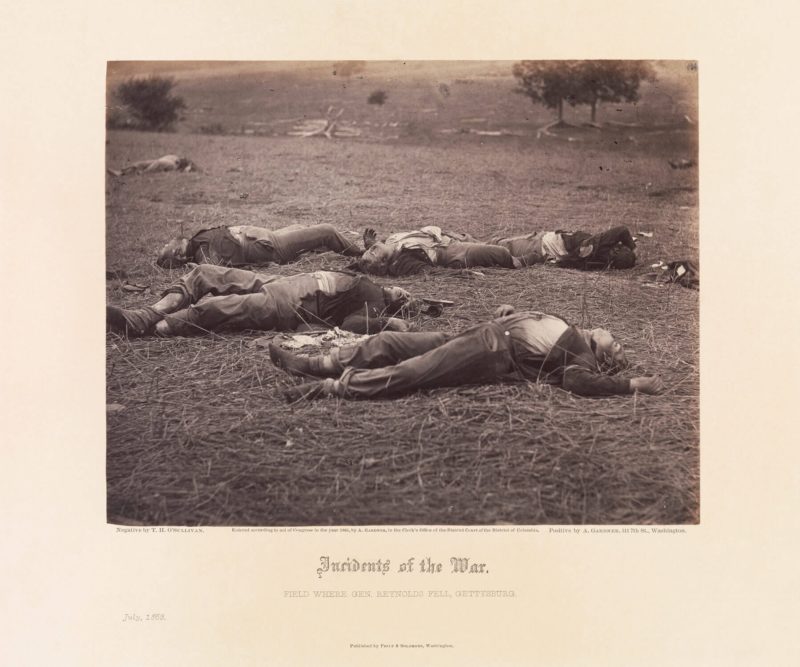

Taken in 1863, this photograph of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg illustrates the horrors of war.

O'Sullivan, Timothy, Field Where General Reynolds Fell, Gettysburg, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org

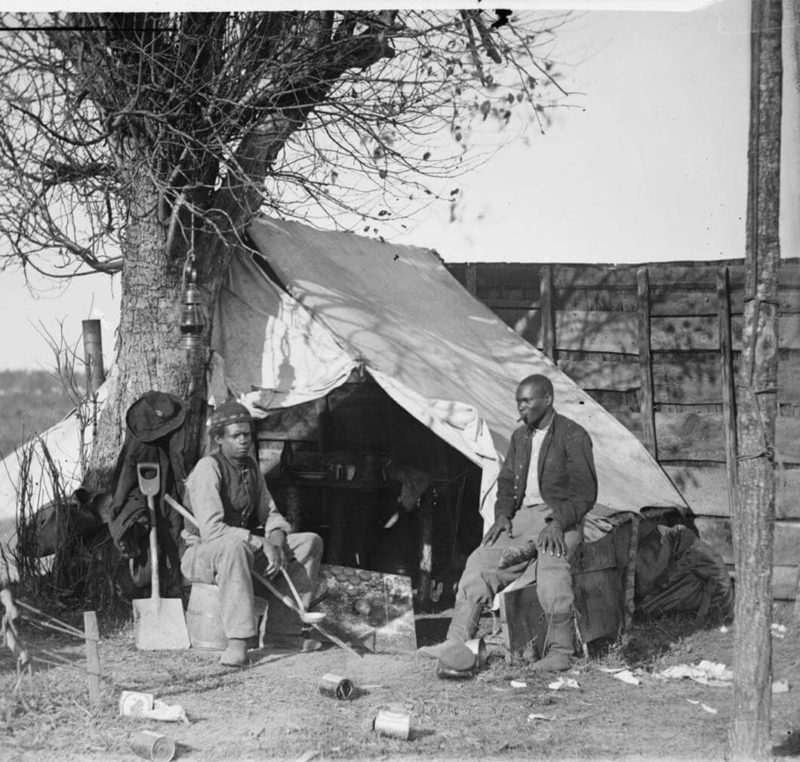

The photograph "Contrabands" features two African American men in Meade, Virginia, near the main theater of war, in 1863. Escaped slaves who allied themselves with Union forces were classified by the government as "contraband of war," and their labor supported Union efforts. In return, they were granted full freedom and were often educated and paid wages.

O'Sullivan, Timothy, Culpeper, Va. "Contrabands", 1863 November. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

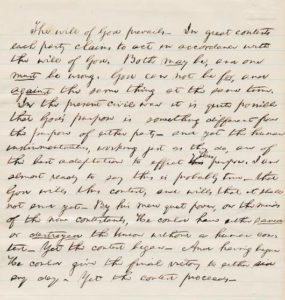

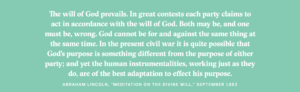

On the heels of a particularly devastating Northern loss, Lincoln began to wonder if God had a higher purpose in mind than upholding the Founders’ original vision. Could it be, he wondered, that God was on neither side of this war? Was it possible that God’s higher purpose was to teach the nation as a whole a difficult lesson about the sins of slavery? Not yet ready to discuss these thoughts publicly, Lincoln penned his “Meditation on the Divine Will” in September, 1862. The thought process outlined in this private writing laid the groundwork for the Emancipation Proclamation, and later for the proposal and passage of the 13th Amendment, which formally abolished slavery in the United States in 1865.

“Meditation on the Divine Will,” Autograph manuscript, September, 1862.

Original document part of McLellan Lincoln Collection at the John Hay Library, Brown University

“Waiting for the Hour” by Wililam Tolman Carlton, 1863.

Wililam Tolman Carlton, “Waiting for the Hour,” 1863. White House History. Retrieved from https://www.whitehousehistory.org

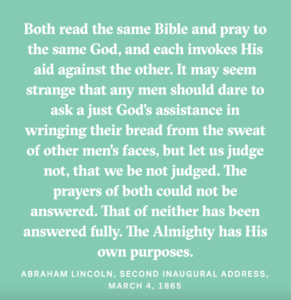

By the beginning of Lincoln’s second term in office, an estimated 620,000 people had lost their lives. The war was coming to a close, with the Union emerging victorious, when Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865. But this speech was not the oratory of a triumphant leader. Given by a president humbled by the realities of war, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural revealed a much different vision of unity than the one he held at the beginning of civil unrest. He presents the North and South as united under the sin of slavery, a sin of which all Americans had been guilty. The God of all nations had judged the behavior of the people, he said, and found it wanting.

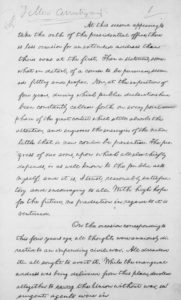

The handwritten text of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.

Lincoln, Abraham, Second Inaugural Address; endorsed by Lincoln, April 10, 1865, March 4, 1865; Series 3, General Correspondence, 1837-1897; The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division (Washington, DC: American Memory Project, [2000-02]). Retrieved from http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/alhome.html

Lincoln delivering his Second Inaugural Address as President of the United States.

Gardner, Alexander, Abraham Lincoln delivering his Second Inaugural Address as President of the United States, Washington, D.C., March 4, 1865, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

As Lincoln had observed in the Second Inaugural Address, the American people were united by an experience of shared tragedy. However, they could also be united in the common goal of healing. His deep biblical reflection in the text of the speech presented a remorseful and generous spirit “to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan.” In appropriating this biblical imagery of healing and restoration, Lincoln encouraged all people to come together to share in the effort of Reconstruction.

Lincoln’s evolving plan following the war was one of mercy and magnanimity. In his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, delivered in 1863, Lincoln offered a full pardon for those involved in the insurrection. It also allowed states to reform their governments once 10 percent of citizens pledged themselves to the United States. Southern states would be re-admitted to the Union as long as they recognized the free legal status of former slaves.

Lincoln was assassinated before he was able to see the results of his plan to unite a nation. But through his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, he left behind a clear indication of his plans for national unity – beginning with forgiveness.

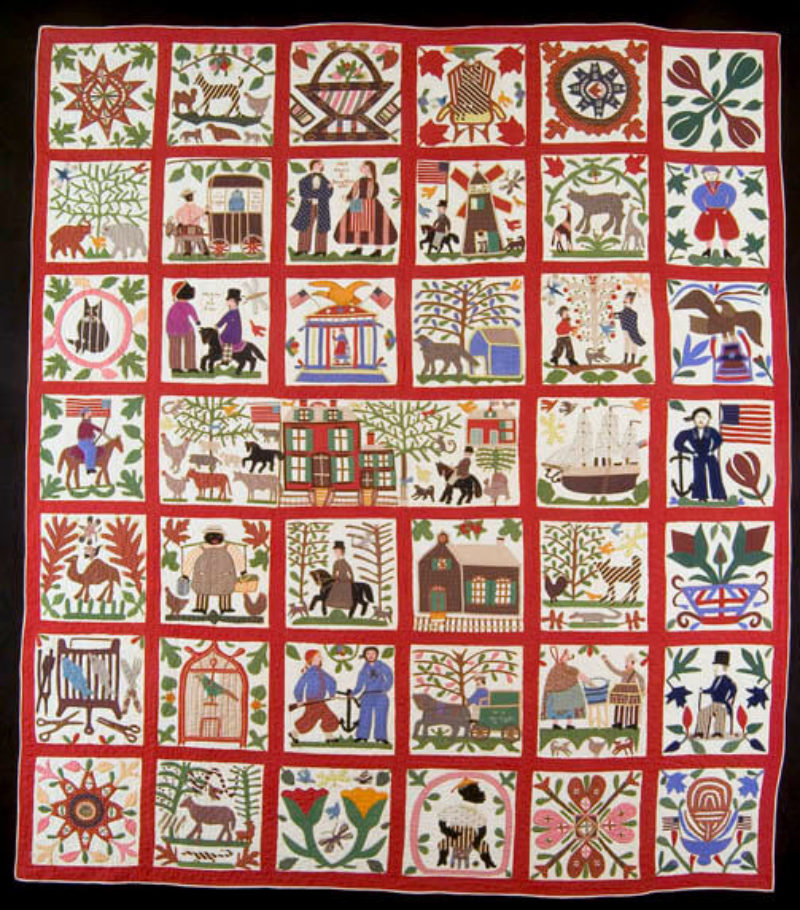

“Reconciliation Quilt” by Lucinda Ward Honstein.

From the International Quilt Study Center & Museum Collection