Credit: Library of Congress

The Newberry Library

Wallach Division Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Boston Public Library

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College (SW09-A0011480)

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Women's Suffrage and Equal Rights Collection, Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Records of the National Woman's Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Records of the National Woman's Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Ohio History Connection. SC 1337

Topical Press Agency / Stringer / Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Peter Stackpole / Contributor / The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) / Museum of the City of New York. 2008.1.10

Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) / Museum of the City of New York

Records of the Christian Holiness Association, Asbury Theological Seminary Special Collections, Wilmore, KY

Library of Congress

Bettmann via Getty Images

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Red Cloud Indian School and Marquette University, Holy Rosary Mission – Red Cloud Indian School Records, 6-1 T 61003

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, NMAI.AC.057, Item N53238

California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Bob Adelman / Magnum Photos

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Joyner Library, East Carolina University

TopFoto / The Image Works

John F. Phillips

Free Library of Philadelphia

Wallach Division Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

SEPS licensed by Curtis Licensing

Milstein Division, The New York Public Library

Alexander Alland, Jr. / Corbis Historical via Getty Images

Bettmann / Bettmann via Getty Images

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom Records, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Photographer unknown / Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.1730

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

National Archives photo no. 512590

Justice is the responsibility of anyone with power, and in America the power of government rests with the people. Building a nation from the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the blueprints of the U.S. Constitution has often involved struggle. Living up to an ideal is difficult. The task is even more complicated when rights compete, when resources are scarce, or when people feel threatened. How do we treat others fairly? How will we live in harmony? How can liberty lead to justice?

These struggles got more complex as more people came to America in the centuries after the Revolution. Slavery, rights of Native Nations, civil rights, women’s suffrage, treatment of workers, and other issues demanded decisive and principled responses. Who deserves what, and at what cost?

In matters like these, with America’s core values at stake, many Americans have looked to the Bible for guidance. There they found encouragement to act justly and to love mercy. Beyond simple fairness, biblical justice includes righting wrongs and restoring harmony. The reason? Each person is valued equally by God. The biblical writers even measure the success of nations and people by their treatment of those who are poor or vulnerable.

We can explore the struggle for justice in America through three lenses—the individual, the community, and the nation—as the nation has worked to get beyond self-interest to pursue the common good.

Defend the poor and fatherless: do justice to the afflicted and needy.

Psalm 82:3

Jump To

Exhibit

Justice begins at the personal level. We treat each other with respect only when we recognize our common humanity. Because of their moral authority, biblical stories and teachings about justice and human dignity have framed debates about slavery, the rights of women, and many other social disputes. “What does the Bible say?” is among the first questions asked. But with lives, identities, fortunes, and even entire economies at stake, agreement has not been easy. People have accused their opponents of misreading the Bible. Despite disagreements, many have found encouragement in the Bible to endure and overcome suffering.

Americans struggled to reconcile the ideal of liberty with slavery. Since biblical times, indiscriminate forced labor for debt, crime, or conquest has been practiced around the world. But in America, slavery became a reprehensible race-based institution.

By law, the enslaved were property rather than people. The brutality and injustice of chattel slavery fueled prejudice and became a pervasive social cancer, provoking passionate debates. Slaveholders and abolitionists cited the Bible in support of their cause. Both could not be right. While slaveholders pointed to passages describing ancient slavery with unspoken approval, abolitionists argued its incompatibility with biblical views of human dignity, justice, and love. Vehement arguments defied resolution and led to the Civil War.

Many enslaved people found dignity and comfort in the Bible. Its stories, especially of the Hebrew Exodus out of slavery in Egypt, gave them faith in God’s justice and the expectation and hope that one day they would be free. They also found strength to endure suffering and guidance to live with integrity. Biblical themes are prominent in the writing and speeches of slaves and former slaves. The work of people like Phillis Wheatley, Olaudah Equiano, and Frederick Douglass captivated readers around the world with a vision of human brotherhood. All people, they wrote, are children of God and deserve respect—and liberty.

So there is no difference between Jews and Gentiles, between slaves and free people; you are all one in union with Christ Jesus. —

Galatians 3:28

Credit: Library of Congress

African American congregation gathered in Zion Chapel at Rockville Plantation in South Carolina, 1861, Osborn & Durbec

The Newberry Library

Portraits of formerly enslaved people, from left to right:

Olaudah Equiano, 1789; Name unknown, ca. 1902; Phillis Wheatley, 1773; Isaiah Montgomery, 1910; Name unknown, ca. 1902

You have no lamp collections from “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?”

Other slaves and abolitionists came to believe that the only way to overthrow the entrenched institution of slavery was to take up arms. Some became vigilantes, calling themselves “holy warriors.” Nat Turner, a slave and preacher, and John Brown, a fanatical white abolitionist, led two notorious and bloody insurrections. Others, animated by a biblical faith, joined military units to combat injustice, like the African Americans of the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Wallach Division Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Engraving depicting a Southern planter arming those he enslaves to resist the abolitionist John Brown's raid, 1859

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Engraving depicting Nat Turner speaking with fellow enslaved people before the rebellion he led in 1831 against white slave owners in Virginia, 1863

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Illustration depicting abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass in an antebellum mob attack, 1892

You have no lamp collections from Armed Resistance?

The furious arguments over slavery divided church denominations and congregations and exposed divisions in interpretations of the Bible. Defenders of slavery saw the text plainly allowing the institution. Abolitionist theologians argued that American slavery was so dehumanizing it could not be compared with the political-economic servitude named in the Bible. What’s more, they said, the forced labor described in the Bible was neither required nor favored by God, who calls all people into freedom. They believed religious people were obligated to fight slavery.

Boston Public Library

Anti-slavery poster, 19th century

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College (SW09-A0011480)

Silhouettes commissioned by Quaker abolitionists, from left to right: David Cooper, unknown; Elias Hicks, 1829; Paul Cuffe, 1817

You have no lamp collections from Abolition and the Churches

Abolition’s ideals of human dignity and individual rights informed the struggle for women’s suffrage. The famous phrase in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” would appear to include all human beings. In practice, however, some protections under law were restricted to male landowners. Women were not allowed to vote and had limited ability to control property and make contracts. The fight for women’s voting rights and equal treatment under law would be long and painful. With both sides appealing to the authority of the Bible, questions of scriptural interpretation were again central.

Women and men often opposed women’s voting because they read in the Bible different social responsibilities for men and women. Anti-suffragists saw women as the “moral caretakers” of society. They championed as indispensably important the role of women in homes, charitable societies, and schools.

But when suffragists read the Bible, they saw a greater imperative for equal participation in politics. They cited Genesis 1:27, which describes God creating man and woman together and putting both in charge of nature. They highlighted female leaders in the Bible, such as Deborah, who once ruled Israel. Suffragists aimed at more than the right to vote. They saw justice as requiring recognition of women as equal members of a democracy and so called on Americans to reexamine biblical texts.

So God created human beings, making them to be like himself. He created them male and female. — Genesis 1:27

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Suffrage parade in New York City, ca. 1913

Women's Suffrage and Equal Rights Collection, Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College

"How Long Will Women Wait for Liberty?" flyer, 1923

Library of Congress

Suffragists casting votes in New York City, ca. 1917

Library of Congress

Headquarters of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, ca. 1911

Records of the National Woman's Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

The suffragist Alison Turnbull Hopkins protests outside of the White House, January 30, 1917

Records of the National Woman's Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Suffragists being arrested for protesting outside the White House, August 1917

You have no lamp collections from Challenging the Social Order

Exhibit

Community justice involves pursuing fairness and harmony among groups of differing faiths, ethnicities, and socio-economic statuses. Balancing competing claims in a diverse society requires thoughtful compromise. Laws need to be just for each person and group in promoting the common good. This task is complicated by changing sources of identity, geographic mobility, and shifting community populations. Are humans defined first as individuals or as persons within families and communities? Of what relevance is the biblical question “Who is my neighbor?” As a source of moral guidance the Bible navigates such issues, helping groups act more justly toward others while safeguarding freedoms and connections.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States experienced immense social and economic change. The expansion of individual rights, the rise of industrial capitalism, new technologies, and the rapid growth of cities transformed the way Americans lived and worked. Many people saw in these radical changes a threat to traditional family life—and the family was seen as a basic building block for healthy communities and a strong nation. Reformers drew on their faith commitments and biblical teachings in organizing numerous programs and movements to protect the family. In so doing, they pursued justice for marginalized groups and vulnerable people.

In the nineteenth century, a national movement emerged to promote temperance—self-restraint from alcohol abuse. Similar to today’s anti-drug campaigns, the Temperance Movement grew as people saw households ruined by violence, promiscuity, crime, poverty, and disease—which were seen as direct consequences of alcoholism. To protect the home, temperance campaigns pushed for changes in laws and attitudes using strategic gatherings and the popular media of the time including books, pamphlets, tracts,and cartoons. The materials were often linked to the Bible. Many temperance activists were leaders in other reform movements like abolition and women’s rights.

Ohio History Connection. SC 1337

Women singing hymns in front of a bar in support of the Temperance Movement, ca. 1873

Topical Press Agency / Stringer / Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Woman's Christian Temperance Union members marching in Washington, DC, in support of prohibition, ca. 1909

Peter Stackpole / Contributor / The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Woman's Christian Temperance Union members demonstrating in a bar, date unknown

You have no lamp collections from “Home Protection”

As the nation industrialized, working-class communities faced severe injustices such as exploitative labor practices, long hours, low pay, hazardous workplaces, and inferior housing. Many lived in crushing poverty. Religiously motivated reformers like D. L. Moody, Dorothy Day, and Frances Perkins organized to remedy these conditions and stabilize working families. They drew on the Bible to remind government and business leaders of the Golden Rule, the Beatitudes, and other teachings of Jesus about the poor and vulnerable. They called on wealthy members of society to become more Christ-like and treat their workers with charity, benevolence, and respect. Others worked to reform labor laws and social systems.

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) / Museum of the City of New York. 2008.1.10

Children living in poverty, ca. 1890

Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA

National Child Welfare Association poster promoting living wages for workers, ca. 1917

Jacob A. Riis (1849–1914) / Museum of the City of New York

Residents of a tenement building in New York City, ca. 1890

Records of the Christian Holiness Association, Asbury Theological Seminary Special Collections, Wilmore, KY

"Slum Sisters" of the Salvation Army, who conducted ministry in low-income urban communities, date unknown

You have no lamp collections from Working-Class Relief

From colonial times, family, church, and school shared responsibility for instructing children in America. A moral grounding in the Bible was common. Tensions surfaced as communities changed and schools welcomed children from an increasing variety of religious backgrounds. People of different backgrounds and religious persuasions had different ideas about how their children should be educated. Increasingly, a secular state-run system emerged. Public education brought its own tensions. Many parents have found its absorption of the family’s and church’s role in moral instruction a threat to family rights. They have responded by homeschooling their children or forming faith-based schools. The role of parental rights in public education is a continuing debate.

Never forget these commands that I am giving you today. Teach them to your children. Repeat them when you are at home and when you are away, when you are resting and when you are working.

— Deuteronomy 6:6, 7

Library of Congress

Political cartoon illustrating anti-Catholic sentiment, 1870, Thomas Nast

Bettmann via Getty Images

Students praying at Seaton Elementary School in Washington, DC after it desegregated, 1954

Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Students outside a schoolhouse in Custer, Washington, October 1893

You have no lamp collections from Education and Parents’ Rights

Some people desire to live in diverse communities; others prefer to live among people much like themselves. But racial bias and enforced segregation deprive minority communities of basic rights and can damage their sense of human dignity. The Bible has played a role in the complex story of American segregation—both in its establishment and in its eventual dismantling. Despite the founding vision of unity and equality, white Americans often used the Bible to justify their attempts to separate themselves from Native Americans, African Americans, and, later, immigrant groups. In time, however, appeals to the Bible—to its overarching call for justice and its mandates for mutual respect—brought people to support desegregation efforts and recognize human rights as gifts of God.

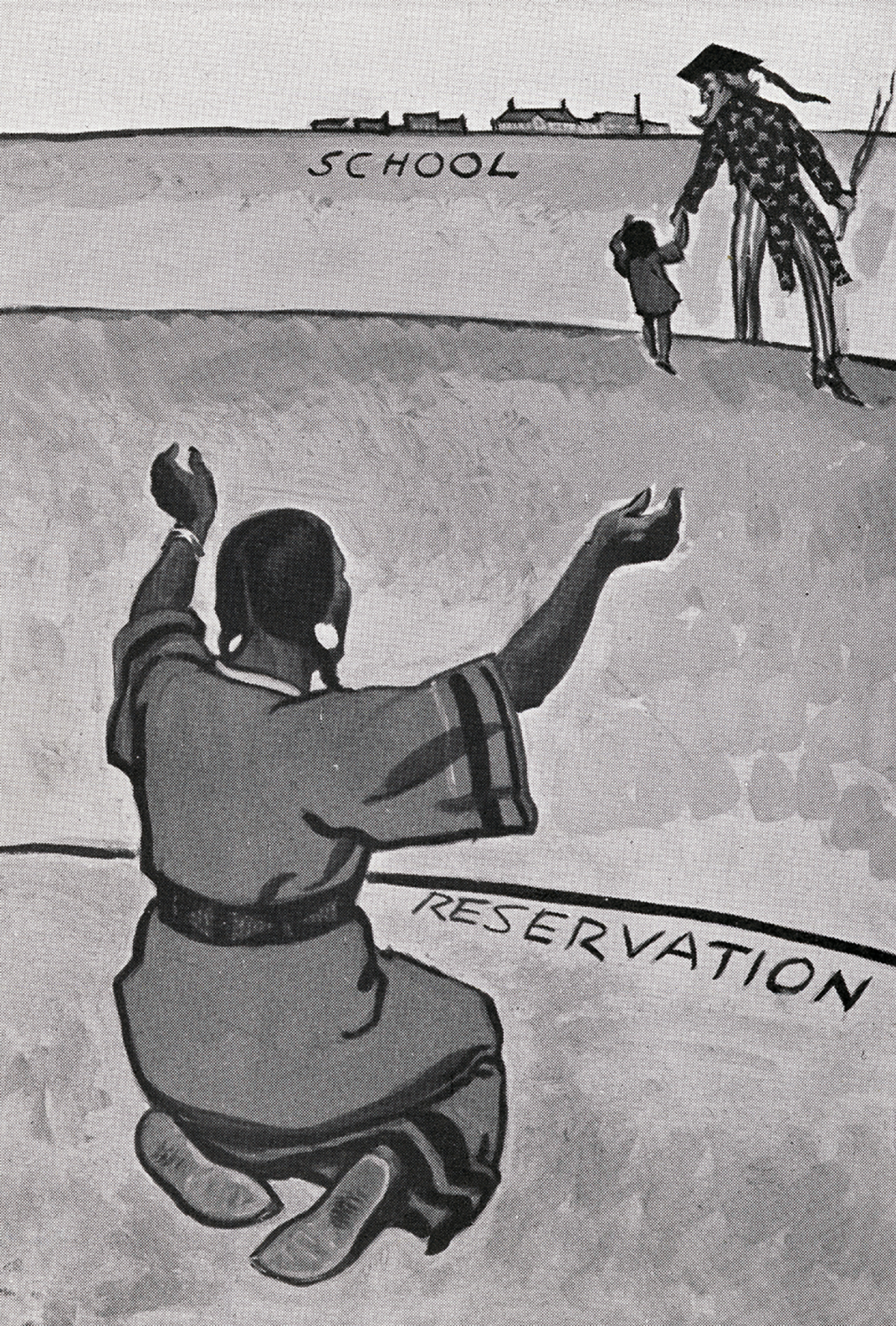

European settlement disrupted Native American communities. Early missionaries tried to win natives as converts to the Christian faith and to assimilate them into the emerging society. Despite efforts by some settlers to establish mutually respectful relations, conflict arose with several tribes as more Europeans arrived needing land. Later, some Americans came to view the customs of native people as threats to the values needed for the nation’s success and to prefer segregation to assimilation. Government officials forced many tribes to leave ancestral lands for distant reservations. Many people, including numerous people of faith, recognized the injustice of these policies and reached out to native communities. Missionaries like Jeremiah Evarts and social organizations like the Indian Rights Association provided aid and advocated for Native Americans’ rights.

Red Cloud Indian School and Marquette University, Holy Rosary Mission – Red Cloud Indian School Records, 6-1 T 61003

Oglala Lakota children praying at bedtime, 1965

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, NMAI.AC.057, Item N53238

Children of Ladies Aid Society members and missionaries sit outside a building on the Mescalero Apache Reservation, 1916

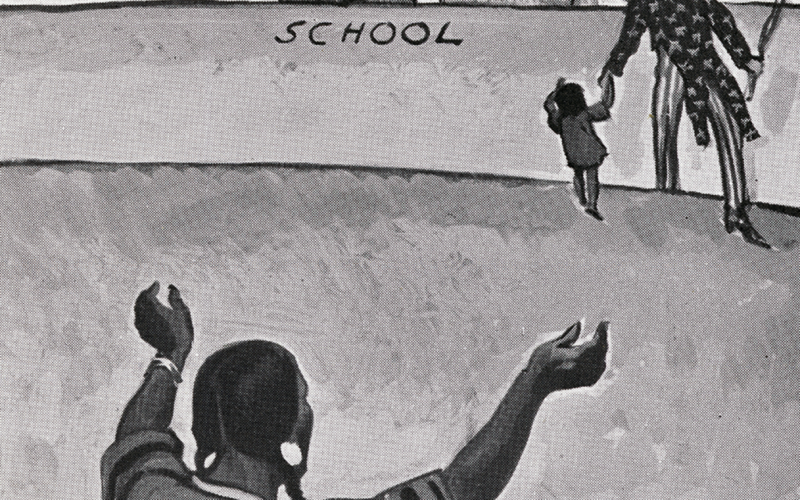

California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Political cartoon illustrating Uncle Sam leading a Native American child away from home and toward a boarding school, 1939, Maynard Dixon

You have no lamp collections from Assimilation of Native Americans

After the Civil War, many states enacted so-called Jim Crow laws that prevented formerly enslaved men and women from exercising the newly recognized civil rights of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Jim Crow laws imposed severe inequities on African Americans and relegated them to a subordinate status. Segregation codes applied to schools, housing, restaurants, hospitals and even cemeteries. The Bible was used as a rationale for many of these injustices. African American churches, however, soon embraced a more comprehensive understanding and vision of biblical values. The modern civil rights movement, led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., drew on this legacy of faith to challenge attitudes of white supremacy and fight segregation. Dr. King initiated an essential conversation about race, reconciliation, and American identity, which was grounded in biblical ideals of justice and brotherhood.

God, who made the world and everything in it, is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples made with human hands … From one human being he created all races of people and made them live throughout the whole earth. — Acts 17:24, 26a

Bob Adelman / Magnum Photos

Police use water cannons against African American protesters in Birmingham, Alabama, 1964

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Sign at a segregated waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, May 1940, Jack Delano

Joyner Library, East Carolina University

Officers from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at a protest in Greenville, North Carolina, J. Thomas Forrest

TopFoto / The Image Works

A woman faints at the funeral for four black girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, September 1963

John F. Phillips

Sisters of Loretto join hands with other demonstrators before a march in Selma, Alabama, March 1965

God, who made the world and everything in it, is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples made with human hands … From one human being he created all races of people and made them live throughout the whole earth. — Acts 17:24, 26a

You have no lamp collections from The Civil Rights Movement

Exhibit

The American Revolution was a cry for justice. After independence, the quest for justice grew more complicated. That struggle was taken up by the U.S. Constitution, with varying degrees of success.

In his first inaugural, Thomas Jefferson called America “the world’s best hope.” The new beacon in the world inspired others to fight for their own independence and build new governments on principles of justice and biblical values. America often supported these efforts with diplomatic, economic, or military aid. In many cases people fled injustice in their home countries, trusting that the U.S. would give them a fair chance to live in peace.

The United States was born out of immigration and has welcomed more immigrants and refugees than any other country. People from around the world come in search of a better life, drawn by the promise of respect for God-given equality and liberty. Delivering on these promises, even incompletely, has led to great innovation and prosperity.

The arrival of successive waves of immigrants led to a persistent tension. What effect would people from so many other cultures have on America’s national institutions and values? In the mid-1800s, two prominent responses to immigration groups emerged—nativism and social ministry. Nativists wanted to maintain American values by restricting immigration. Social ministry activists tried to put those values into practice by caring for immigrants and helping them integrate into the wider society.

A large wave of immigration in the mid-1800s introduced people from a broader mix of faiths and nationalities to the United States. Nearly half of these newcomers were Irish and German Catholics. Their arrival alarmed many native-born citizens, who feared that the Catholic immigrants’ competing loyalty to the Pope would undermine America’s democracy. Anti-Catholic riots in several cities, including Philadelphia, left people dead and churches burned to the ground. These fears were countered by other voices that urged openness and justice, pointing to the Bible’s instruction to welcome strangers.

Free Library of Philadelphia

Lithograph illustrating a riot against Irish Catholic immigrants in Philadelphia on July 7, 1844, H. Bucholzer

Wallach Division Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

Satirical cartoon titled "The Modern Ark" depicting immigrants entering the United States, 1871, Ezra Bisbee and Solomon Eytinge

SEPS licensed by Curtis Licensing

Anti-immigration cartoon titled "Make This Flood Control Permanent," depicting a wave of "alien undesirables" behind a wall, 1917, Herbert Johnson

Do not mistreat foreigners who are living in your land. Treat them as you would an Israelite, and love them as you love yourselves. Remember that you were once foreigners in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God. — Leviticus 19:33–34

You have no lamp collections from Nativism in a Nation of Immigrants

Between 1870 and 1914, a second wave of immigration brought more than 20 million people to America. They included large numbers of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. Most crowded into urban slums, worked in factories and mines, and endured severe poverty. To ease the assimilation of so many people in dire need, interdenominational social ministries stepped in to provide material help—including food, clothing, education, and job training. Acting on biblical mandates to show love for foreigners and care for the vulnerable, these organizations provided vital community services. They also resisted nativist rhetoric and appealed to core American and biblical values in an effort to broaden the national identity.

Milstein Division, The New York Public Library

An Italian family in a Chicago tenement building, ca. 1920, Lewis Wickes Hine

Alexander Alland, Jr. / Corbis Historical via Getty Images

Shantytown along Houston Street in New York City, date unknown

Bettmann / Bettmann via Getty Images

People living in poverty on the Lower East Side, New York City, ca. 1890, Jacob Riis

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection

A family working in a tenement building on Thompson Street in New York City, January 1912, Lewis Wickes Hine

You have no lamp collections from Social Ministry

Many Americans have believed that the United States has an exceptional place among the world’s nations. From the arrival of the first religious dissenters, American colonists understood themselves as set apart by God’s providence. God had led them to establish a “city upon a hill,” and other nations would be watching. People soon came to view the American experiment as blessed by God. By the nineteenth century, national rhetoric embraced this exceptionalism. The nation’s “manifest destiny,” to spread its values and institutions across the continent, spilled over into foreign policy. But exceptionalism also bound the nation to a higher standard. Even as its power grew, its foreign policy needed to align with its core principles. America might be responsible as a force for good around the globe, but how should this be done?

During World War I, the United States emerged as a global power. This new prominence stirred passionate disagreements within the country. President Woodrow Wilson believed America had a moral responsibility to help other countries fighting for liberty and justice—even if that meant using military force. Many others, including Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, wanted to avoid foreign entanglements and favored strict diplomacy, neutrality, and pacifism. People on both sides believed in American exceptionalism and the nation’s responsibility to defend democratic values. People on both sides accepted Scripture as their moral guide. They disagreed about how to advance these values and how to define the limits of the nation’s obligation to act justly. These issues are still being debated.

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom Records, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom demonstrators, likely in Philadelphia, ca. 1920

Photographer unknown / Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.1730

Rev. William Wilkinson, known as the "Bishop of Wall Street" leads the Liberty Loan Choir in a rendition of "America" at New York's City Hall, ca. 1925

Library of Congress

President Woodrow Wilson addresses Congress before the United States entered World War I, February 3, 1917

Library of Congress

Cartoon depicting the negative response to America's neutrality at the beginning of World War I, ca. 1914, William Allen Rogers

National Archives photo no. 512590

"The Prayer of Millions," calling on America to protect those in need during a time of war, ca. 1917

If you obey the Lord your God and faithfully keep all his commands that I am giving you today, he will make you greater than any other nations on earth. — Deuteronomy 28:1

A city built on an hill cannot be hid. — Matthew 5:14b

You have no lamp collections from Intervening in World War I

Justice seeks fairness for all.